Nigeria: Crypto Utopia?

The promise and perils of life after fiat in Africa's largest economy.

Working in the crypto industry is sometimes embarrassing.

In a time when artificial intelligence is being used to cure diseases and usher in an age of abundance, it seems like a waste of our talent and energies to focus on selling ape pictures.

But there are also moments – and they can be fleeting – when I’m proud to say that I work in crypto. There are moments where the promise of this technology and its ability to aid both human liberation and human coordination feels urgent, feels righteous.

Holding space for both of these realities is exhausting.

Because while GPT4 changes workflows on a daily basis, many of the promised benefits of crypto - expanding financial inclusion, funding democratic political movements and enabling new types of communities – are often more theoretical than they are real.

But that’s not entirely true. Because these benefits of crypto are appearing in real life. They just are appearing outside of the United States. And that’s a problem for the work we do here in advancing the underlying technology.

It’s a problem because it allows crypto critics to ignore the benefits of crypto technology. And it’s a problem because it allows crypto ideologues to pretend that blockchains accomplish more than they actually do.

But when you look to markets where crypto is having a real and important impact, you come away with a nuanced story. You see a technology that is solving real problems. You see a technology that can have a massive impact.

But you also see a technology that is far, far from ready for primetime. So, no, we probably shouldn’t be hoping for Bitcoin to replace the US Dollar anytime soon.

Still if you want a glimpse of what a crypto future might look like, you can join me for a quick trip to Nigeria.

Welcome to Nigeria

The first thing to know is that Nigeria has a lot going for it. Nigeria has both the largest economy ($376B GDP) and largest population (213M people) in all of Africa.

Nigeria’s economy is diverse. While its largest export is oil, that industry accounts for only ~6% of GDP. Instead, farming and the service industry are the largest sources of income. It also has a strong creative industry – Nigeria’s film industry produces more films than Hollywood, and its tech sector has produced some winning fintech companies including Paystack (a 200M 2020 Stripe acquisition). The large Nigerian diaspora also sends home massive amounts of money via remittances – almost contributing as much to GDP as the oil industry.

But those strengths should not obscure the very real crises – some natural, some manufactured through mismanagement– facing the Nigerian economy.

Nigeria’s problems started because it remains a massive net importer. As a net importer, Nigeria’s Central Bank wants to keep the Naira (Nigeria’s currency) strong. They have done this by enforcing an artificially high exchange rate. In market conditions, the US Dollar is valued at roughly 760 Naira. But the Central Bank of Nigeria forces banks and foreign governments to value 1 USD at 460 Naira. That means that the Naira’s government enforced exchange rate is 63% stronger than its actual true value.

Why would Nigeria do this?

Well, two reasons.

First, a strong currency is considered essential to attracting the kind of foreign investment that Nigeria needs to improve its agricultural practices and its manufacturing base.

Second, a strong currency means that Nigerians can more cheaply purchase things from abroad. If the Dollar suddenly became worth 5 times as many Euros, we would all be buying a lot of things from Europe. Since Nigeria is a net-importer, this is a pretty important benefit for raising living standards.

But making importing cheaper is also dangerous for Nigeria’s domestic industries. Because when things are cheap to import, there’s not much reason to buy domestic products. Hence why we don’t make many TVs in America anymore.

To support their domestic industries, Nigeria has implemented strict controls on imports. Here’s the US Department of Commerce describing those restrictions:

“Nigeria has an effective duty (tariff, levy, excise, and value added tax (VAT) where applicable) of 50% or more on over 80 tariff lines. These include about 35 tariff lines whose effective duties exceed the 70% limit set by ECOWAS. Most of these items are luxury goods such as yachts, motorboats, and other vehicles for pleasure (75%), as well as on alcohol (75% to 95%) and tobacco products (95%). In addition, Nigeria places high effective duty rates on imports into strategic sectors to boost the competitiveness of the local industries. In agriculture, wheat (85%), sugar (75%), rice (70%), and tomato paste (50%). In the mining sector, salt (70%) and cement (55%).”

The results of these policies — an overvalued currency and strong import controls— is tragic and predictable. Most of Nigeria’s economy has moved into smuggling and underground activity to avoid government enforcement.

Nigeria has one of the largest black markets in the world. That black market does not just cater to drugs or contraband. It represents, according to the ILO in 2018, over 50% of Nigeria’s GDP and 93% of all employment.

That’s insanity. Nine out of every ten people that work in Nigeria are employed under-the-table.

On the one hand, that is a clear sign of economic mismanagement. On the other hand, it’s pretty hard to correctly manage an economy when 90% of it is out of government reach.

How do regulators improve an economy when 90% of labor is not taxable, and 50% of the economy can safely ignore your monetary policy?

They can’t. They also can’t stand-up the basics of a functioning financial system.

That’s why only 3% of Nigerians have access to a credit card. That’s why only 45% of Nigerians have a bank account. That’s why, despite government intervention, inflation regularly exceeds 20% per year.

The government has taken big steps to try to improve its financial system. They have tried giant new initiatives to bring the black market out of the shadows. But those efforts have either been ignored or made things worse.

In 2021, the government introduced the eNaira (the world’s first large-scale Central Bank Digital Currency – real money on the blockchain) to increase financial inclusion. Less than .5% of Nigerians adopted it.

In 2022, the government announced a new design for Naira notes to force Nigerians to bring in and exchange old currency at banks. They hoped this would force Nigerians to participate in the legitimate financial system. That caused a cash crunch and general panic. It has done an estimated $43B in damage to the economy so far this year.

All of this is to say: fiat currency is badly broken in Nigeria.

If only the people of Nigeria had an alternative to their broken fiat system.

If only there were some kind of decentralized currency that could bypass unhelpful and ineffective policies that, in turn, would force the Central Bank to behave more responsibly.

If only there were a way for Nigerians to access currencies like the US Dollar or Euro that are more likely to keep their value so that they could save, build capital, invest and create a functioning financial system.

If only, the people of Nigeria had… well… I guess… crypto?

The Bull Case

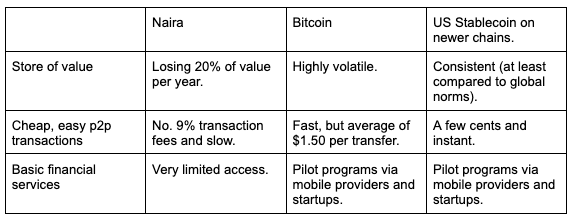

In our ideal world, the people of Nigeria would have a functional financial system with the following properties:

A stable store-of-value currency that attracts investment and encourages saving.

A financial technology stack that enables peer-to-peer transactions with both businesses and via remittances for low or zero cost.

A set of market-appropriate financial services including credit products and investment products.

Clearly, Bitcoin and stablecoins are more attractive than the existing system.

This comparison isn’t theoretical. It’s one that Nigerians are making every day. And they are voting with their wallets.

Nigeria has the highest rate of per capita ownership of crypto (17-24%) anywhere in the world. That’s incredible when you consider that only 51% of Nigerians have internet access. Put another way, 35-48% of all Nigerians with internet access use crypto. Only 40% of Americans with internet access have an Instagram account.

That’s a lot of crypto owners.

But owning cryptocurrency does not mean that you are using it. In fact, in our world owning cryptocurrency just means that you are hoping someone else will buy it for more money than you did. So are Nigerians actually doing anything with their currency?

Yes.

They are using it to save. When your currency is losing 20% of its value per year, and Bitcoin seems to gain value (albeit in a volatile way) while stablecoins seem to hold their value, crypto savings is safer than cash savings.

The Nigerian Diaspora is using it for remittances – the cross-border payment of income to friends and family back in Nigeria. That’s a big deal. Remittances in Nigeria account for as much GDP as their oil exports. And remittances are expensive.

In 2020, Nigerians spent $2.94B in bank fees to send $34B of remittances to family back home, according to the World Bank. In 2021, crypto remittances began to catch fire. In one survey of Americans, 23% of remittances sent from the United States (to any country) used cryptocurrency. In 2022, when “official remittances” via banks dropped by ~$6B, most experts concluded that the $6B in remittances had not disappeared, it had just been sent via crypto instead.

Back home in Nigeria, it is also being used for daily transactions. Crypto transactions in Nigeria are 10x more likely to be used for actual peer-to-peer spending than they are in the United States. In H1 2022, Paxful, the largest platform at the time, reported that Nigerians transaction volume was $400M. That equated to 60% of crypto trading volume in the country ($700M). Daily transactions in crypto were nearly as common as crypto investing.

Crypto has not, however, created a functioning alternative banking system for most Nigerians. But there are early signs of promising, localized solutions that could offer credit and investment products to the 55% of the country that lacks a bank account.

Small peer savings groups, often called esusu, allow individuals in lower-income communities in Nigeria to access capital for opening businesses. These groups allow members to pay part of their income into a shared pool for the opportunity to take turns accessing the shared pool and have been quick to adopt stablecoins as a way to ensure that members who take later-turns are not receiving less value due to inflation.

And technical innovators are rushing to bring financial services via blockchain to the broader Nigerian unbanked. Tingo Group has partnered with the MELD protocol to enable small (~$20 USD) loans to farmers in their network, though data on that partnership has been limited thus far.

The Bear

That’s the promise of a crypto Nigeria. But it’s never all good news.

Stablecoins, for example, are a key element of any future decentralized financial system operating in Nigeria. But many stablecoins are not… exactly… stable. Last May, for example, Terra was one of the most popular stablecoin options in Nigeria. When it collapsed, it not only wiped out the speculative bets of American crypto bros, but the savings of the Nigerians who trusted it. Today, the most popular cryptocurrency in Nigeria is Tether. And Tether is often called the ticking-time-bomb at the heart of crypto markets.

Furthermore, adoption, while surging in relative terms, remains low in absolute terms. And Nigerians, in the midst of all of their other economic woes, now have to contend with choosing among 7 different currencies as their unit-of-exchange (USD, Tether, Bitcoin, old Naira (valued at official or parallel market rates) or new Naira (valued at official or parallel market rates)).

The role of currency as a simple, shared mechanism for facilitating exchange is severely undermined in a world where multiple currencies are constantly shifting value against each other.

It’s also worth acknowledging that undermining government policies – even when they are incompetently executed – is not exactly an ideal outcome of cryptocurrency (unless you’re really an anarchocapitalist…). In Nigeria, the parallel market for blackmarket currency and cryptocurrency undermines the ability of an elected government to tax, to regulate, and to use monetary policy to achieve shared goals for the Nigerian people.

At the same time, the presence of these parallel markets makes it far easier for opponents of Nigeria’s liberal government, including the dangerous terrorist group Boko Haram, to finance its operations. To be very clear, money laundering and terrorist financing existed in the black market long before Satoshi implemented a blockchain. But the continued growth of unregulated financial systems (even those where the government can view transactions, if not block them) makes the task of criminals easier. It might even make us long for the day where the most embarrassing thing about cryptocurrency was speculation on Ape JPEGs or literally anything Sam Bankman-Fried says or does.

Because here’s the thing – the promise of this technology is, in fact, transformative. The open question is whether we’re transforming the world into a place that’s better than the world we have today. If Nigeria is any indication, we still have a long way to go.