Losing Our Religion: Myth & Meaning in the Internet Era

Existential angst in America. The collapse of the old myths. The rise of new cults. The hope for reinvigorating and renewing meaning in online communities.

Sorry for the delayed send on this one — as you’ll see, it’s a bit more complex than some other subjects that we’ve dove into and I wanted to get it right. Hopefully I did that.¯\_(ツ)_/¯ - Alex

When I was seventeen, my friends and I used to spend a lot of time in, my friend, Stephen’s basement. We did what pretentious kids do. We stayed up late and talked about big ideas. We spoke with the kind of confident understanding of life’s mysteries only afforded to teenagers. One night, Stephen's Mom gifted us all copies of Viktor Frankl’s holocaust memoir Man’s Search for Meaning.

Y’know – typical teenage stuff.

It took me a decade to crack it open. The book explores why– aside from dumb luck– Frankl was able to survive the Camps while others lost the will to live. He writes that the people who survived were those who had a clear reason to continue living. Those who had a why could bear any how.

Frankl's experience, and his training as a psychiatrist, informed his development of logotherapy. This is psychotherapy by existential quest. We find meaning by creating it.

As he poignantly writes, “Success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side effect of one's personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one's surrender to a person other than oneself.”

As dispiriting as our day-to-day may seem – pandemics! Roll-backs of rights! Global climate catastrophe! – None of us live in a world as dark as Viktor Frankl’s.

We tend to be myopic in the face of our contemporary challenges. So a little perspective is always worthwhile.

As Emily St Mandel writes in her excellent novel, Sea of Tranquility:

“I think, as a species, we have a desire to believe that we’re living at the climax of the story. It’s a kind of narcissism. We want to believe that we’re uniquely important, that we’re living at the end of history, that now, after all these millennia of false alarms, now is finally the worst that it’s ever been, that finally we have reached the end of the world.”

So no, despite the loudest voices on Twitter, it’s probably not the case that the world is really falling apart this time! But there is truth embedded in our general angst. Our feelings, as my therapist would say, are valid.

Because while it may not be the case that our circumstances are more dire, it is absolutely the case that we are less capable of dealing with them.

According to the General Social Survey, Americans are less happy than at any point since the survey started tracking fifty years ago:

And this unhappiness has real consequences. In 2019, the Senate Joint Economic Committee published a report on the long-term trend in Deaths of Despair. Those are deaths caused by suicide or substance abuse. And while the opiate epidemic is the clear proximate cause of our most recent spike, it's not the only one. The trend appears outside of just drug deaths. It's troubling, to say the least:

And all of this has been happening at a time when things are – on an absolute scale – getting a lot better!

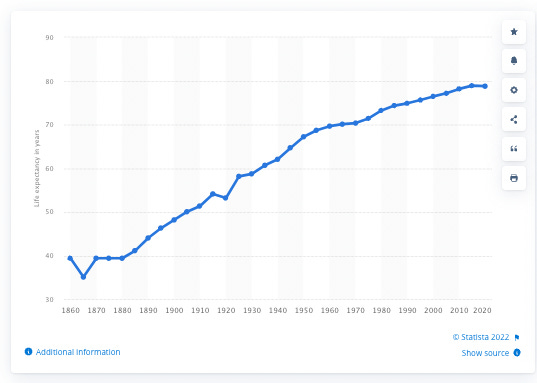

Life Expectancy From Birth (1860-2020):

Growth in US Per Capita Income:

So we’re living longer. We’re richer. But we’re also all in a state of despair?

Seriously, what the fuck?! Are we just ungrateful?

Maybe. But I think there’s a broader crisis at play here, too.

Losing Our Religion

Much to the chagrin of my father, I’ve never been that religious. Do I believe in God? I don’t know - sometimes, I do. Usually when the Eagles are playing.

But I’ve always had a healthy respect for the psychological mechanisms of religion. On a sabbatical from Facebook in 2019, I read a series of interviews with Joseph Campbell called The Power of Myth. Campbell was a comparative religion and literature scholar at Vassar.

He had this idea that it was no coincidence that religions told many of the same stories. He saw universal themes in their narratives. Mythology, he said, had four primary purposes:

The mystical function - filling you with a sense of awe;

The cosmological function - explaining the mysteries of the Universe (where it finds itself in conflict with science);

The social function - providing a sense of social order and reinforcing existing power structures;

The pedagogical function. As he put it, “ of how to live a human lifetime under any circumstances.”

This last function is critical. The role of great narratives - political, religious, historical or even fiction - is to contextualize our experience. It helps us connect our day-to-day with a “why” that transcends the present moment.

We are not just a random collection of particles. We are part of a family, a community, a nation, a grand struggle between good and evil. We matter.

Religions certainly offer these narratives. But grand narratives exist in secular spaces, too. What matter is that there is a narrative that connects our experience to a bigger picture. I call these unifying narratives “Social Myths.” I believe they help give our lives meaning.

Social Myths share a lot in common with their theological cousins. But rather than deriving their authority from a divine creator, they derive it from a Big Idea. What they have in common with religion is four components:

Axioms of faith that make their believers feel like they are on the right side of a dispute: God wants us to act like this! America is good! Economic growth is always right! Those people are racist! Freedom is always better than constraint! All wealth is immoral!

A sense that individual actions/rituals can make a difference: I can be a good person! I can convert others to live better! I should work harder! I should post about this on social media! I will donate!

A vision of ultimate triumph/reward: We will reside in the Kingdom of Heaven! We will spread our values around the world! We will get everyone out of poverty! We will outlaw Billionaires!

A community of influencers and regular people that cement your identification within the group.

My theory is that our mental health crisis is a spiritual crisis. We have lost our connection to the Social Myths that bound humanity before the modern era.

Religion is in precipitous decline in much of America:

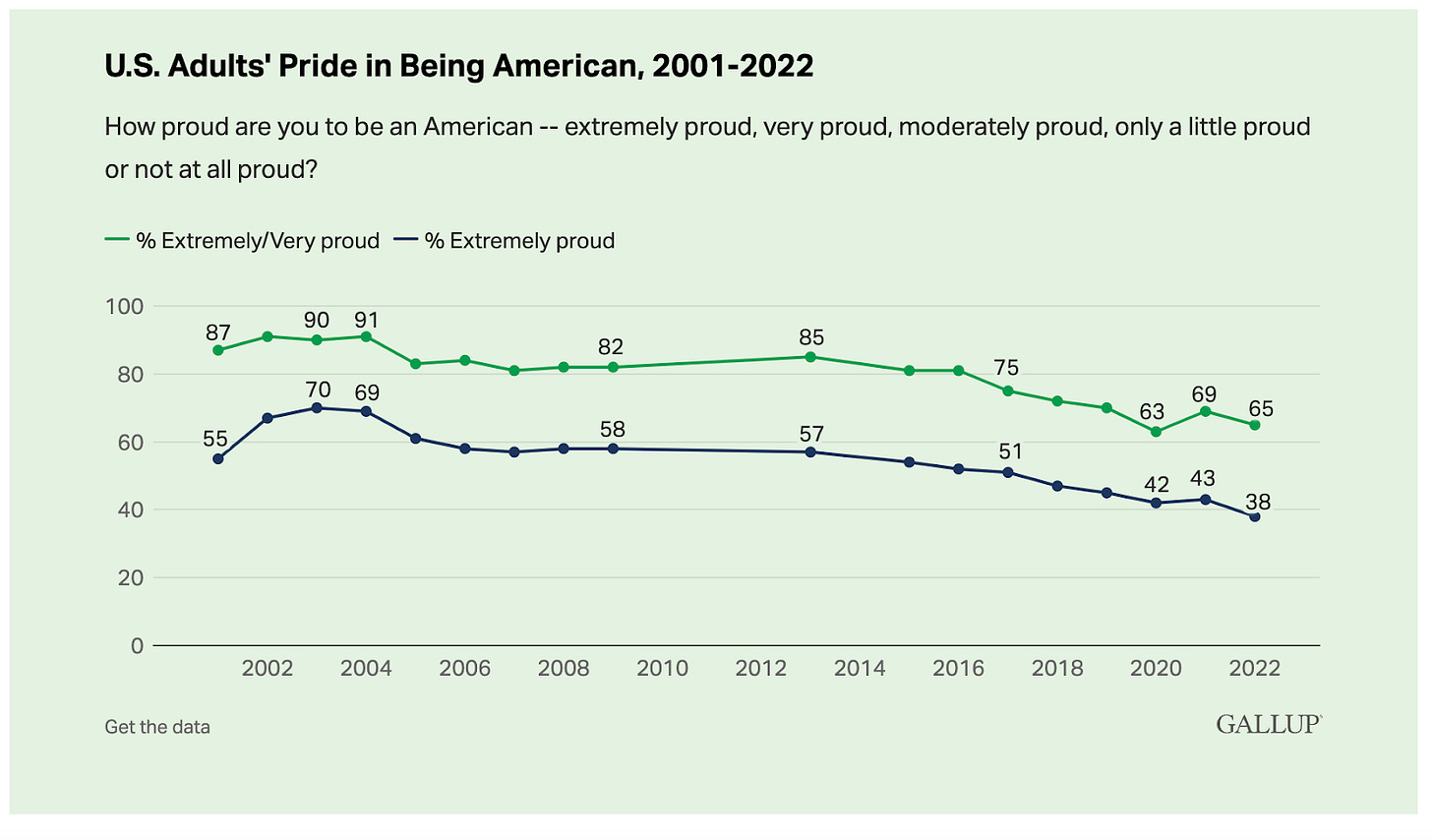

Americans pride in their national identity has been in decline since the patriotic fever-days after 9/11:

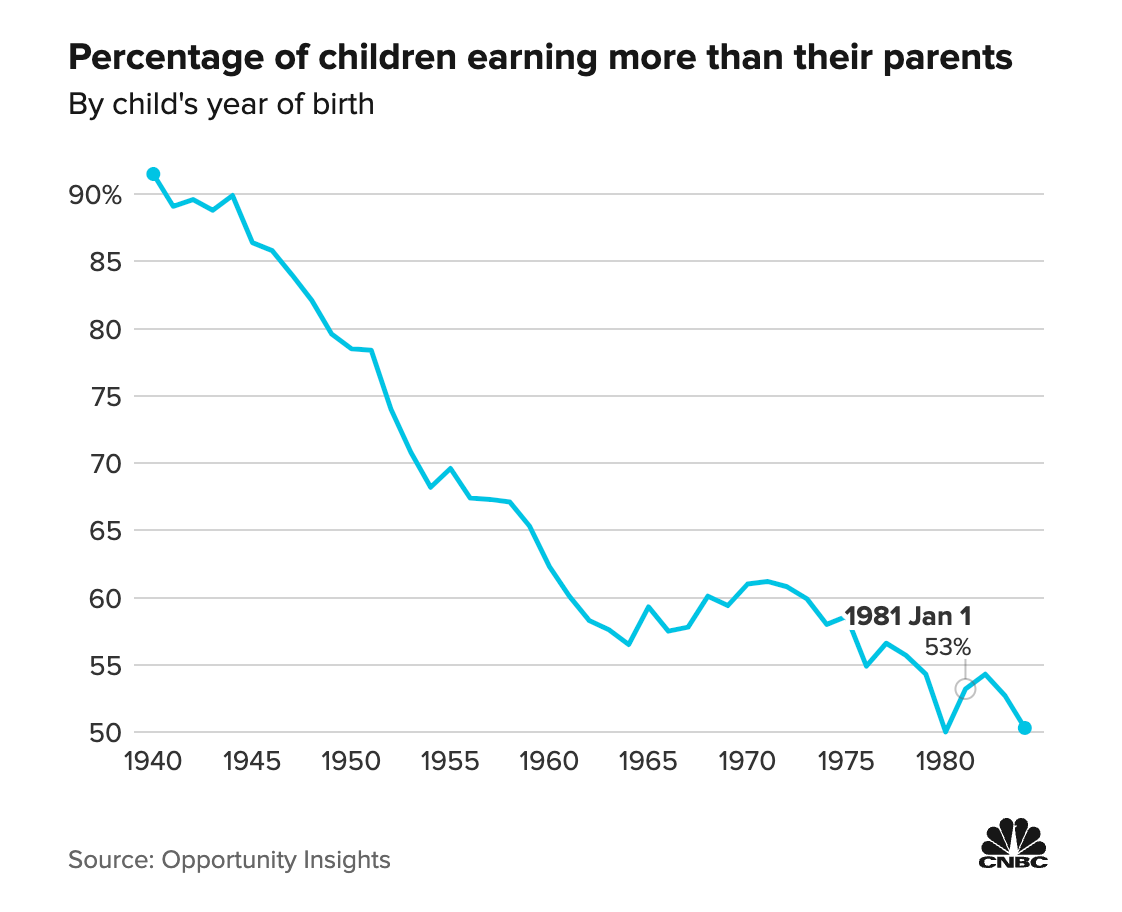

And our confidence in the Church of Capitalism and Progress – the idea that free enterprise will make kids better off than our parents – is eroding. In a 2021 survey, only 32% of Americans thought that kids would be better off financially than their parents. And there’s evidence to back that up:

The triumph of individualism has delivered tremendous victories for civil rights, for prosperity, for freedom. But it has come at a cost. The detachment from our old stories has created an existential void. It is, as Frankl writes, a subtle paradox:

"The more one forgets himself--by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love--the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself. What is called self-actualization is not an attainable aim at all, for the simple reason that the more one would strive for it, the more he would miss it. In other words, self-actualization is possible only as a side-effect of self-transcendence.”

The more we have focused on ourselves, the less happy those selves have become.

So is this all the fault of the Internet? Well, these narratives were shifting long before the internet. But it is true that the breakdown in old narratives accelerated in the Internet Age. And that’s well precedented.

The era of the printing press was the era of the Protestant Reformation and endless religious wars in Europe.

The era of the radio and television gave birth to mass political movements from fascism to the Civil Rights and Anti-War movements of the 1960s.

The internet… well…

We know that it’s caused some chaos. But it’s also created a new generation of small, divisive ideological groups. They’re less Social Myths than Social Cults.

But, in their rough (and often regrettable) experiments, we can see the seeds of new Social Myths that will light our way through the 21st Century.

The Social Cults: Q and Bitcoin Maximalism

There’s an idea in technology that any new product needs early adopters. These are the people whose need for the product runs so deep that they overlook glaring flaws in its early versions. It is best expressed by Reid Hoffman’s adage: “If you are not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you've launched too late.”

Our social cults definitely have some embarrassing moments (Bitcoin) and sometimes are just plain embarrassing (QAnon). But, like any successful MVP, they have a clear appeal to those who need what they’re selling. They find product-market fit despite their obvious flaws and shortcomings.

For those of us who are less alienated, these communities look like cults. We are privileged to not be so disillusioned with the world that we need the first version of new beliefs. But in their viral success, we can learn the internet-native tactics that will power the next generation of Social Myths – even as we shake our heads at these particular congregations.

The Prophecies of Q: Religion as Video Game

QAnon started with a single post on the 4chan message board in October, 2017. The anonymous poster claimed to be a “Q-Clearance Patriot” (a reference to a security clearance in the Dept. of Energy). He posted hints (“crumbs”) about a forthcoming “Storm” where Trump would arrest his political opponents for satan worship and pedophilia. Yes, really.

This kind of thing happens all the time on the internet.

But this narrative started to catch on. People began to believe that Q was really reporting from the inside of a massive conspiracy. Never mind that his predictions never came to pass.

The Q Faithful did not waiver.

Why did Q attract so much attention and receive so much loyalty?

For that question, we can turn to a fellow practitioner of the Dark Arts of Conservative Media, Steve Bannon. Before becoming Trump's chief propagandist, Bannon spent time working in online games. Jennifer Senior writes:

“[Bannon] notes how stunned he was to discover how many people played multiplayer online games, and how intensely they played them. But then he breaks it down for Morris, using the example of a theoretical man named Dave in Accounts Payable who one day drops dead.

“Some preacher from a church or some guy from a funeral home who’s never met him does a 10-minute eulogy, says a few prayers,” Bannon says. “And that’s Dave.”

But that’s offline Dave. Online Dave is a whole other story. “Dave in the game is Ajax,” Bannon continues. “And Ajax is, like, the man.” Ajax gets a caisson when he dies and is carried off to a raging funeral pyre. The rival group comes out and attacks. “There’s literally thousands of people there,” Bannon says. “People are home playing the game, and guys are not going to work. And women are not going to work. Because it’s Ajax.”

“Now, who’s more real?” Bannon asks. Dave in Accounting? Or Ajax?

[....] Yes, [Bannon] told me. That’s just it: “I want Dave in Accounting to be [a video game warrior hero] in his life.”

But that’s precisely what happened on January 6. [...] The fantasy and the reality had become one and the same.”

QAnon was not religion as sermon or text. It was religion as massive, collaborative game.

It welcomed and validated new players as righteous patriots. It painted a vision of an assured utopian future. It offered rituals and quests to participate in the Great Struggle. It crowned a clergy of true believers that the faithful could interact with and trust.

It built an entire alternate reality. Facts were no match for the power of its players’ imaginations. And how did it work out for them? Well, in 2021, a survey found that 15% of Americans believed that Q was correct.

In other words, in four years, QAnon convinced 15% of Americans that their political opponents were satan worshiping pedophiles.

Yeah, that's one scary-ass death cult. But it also highlights how hungry people are for big stories where they can be heroes. Our project should be to give them narratives that can fill that psychological need while -- y'know -- not threatening the world with insanity.

Bitcoin Maximalists: A New Gospel of Wealth

Bitcoin is not the first movement to bind ideological adherence and profit. That distinction, at least according to Max Weber in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, goes to the Puritans. Puritans saw hard work and wealth as signs that a person was divinely selected.

Bitcoin adopted this idea. But then just did away with the pesky hard work bit in favor of a whole lot more wealth.

Bitcoin was, at first, a populist rejoinder to Wall Street. But it's leftwing roots were gradually cast-aside in favor of a libertarian ethos. That's at least partially because it had this neat trick that we call “number go up.”

For those who were willing to buy into its narrative of war with corrupt governments and bankers, Bitcoin offered a pretty nice miracle. All you had to do was hold onto your coin, and ideally, keep them beyond the reach of government in a “self-custody” wallet. If you did that, you would be rewarded with astronomical yields.

Of course, Bitcoin price has halved in the last year. But in the last 10 years, it has offered a neat 200,000% return.

The Promised Land is accessible via your private key. Who knew?

So whereas Q promised its adherents an apocalyptic struggle and eventual utopia, Bitcoiners received the dividends of heaven on a rolling basis.

This wealth also had a particularly powerful viral factor. Because, you see, adherents could demonstrate their commitment to the faith through displays of wealth.

At the expense of traditional good taste, the Church of Crypto saw epic wealth as a sign of piety. So members were encouraged to post their financial windfalls. They were expected to purchase expensive NFT relics and display them. These were the acts of true believers.

And, in a beautiful viral feedback loop, displays of wealth attracted neophytes to convert to Bitcoin buyers. This, of course, further drove up the price. The crypto maxim “WAGMI” expresses this idea: if we all are faithful to the Church of Hodl we will be rewarded. 🙏

By tying spiritual purpose with material wealth, Bitcoin is the first belief system with a built-in monetization strategy.

Our Satoshi who art on-chain...

A New American Pantheon

Of course, it’s unlikely that Q or Bitcoin Maximalism are going to become the dominant spiritual revolutions of our time.

Even in today’s topsy-turvy political culture, there are natural limits to the obvious lies people internalize (Q) or the interest-level in deflationary monetary policy (Bitcoin). But internet culture means that we don't need universal churches. Meaning -- like pop culture before it -- is becoming a highly personalized pursuit.

The lesson of Q and BTC is that the tactics for collaboratively constructing meaning is different in the internet era.

From Q, we see the power of a motivated community playing a collaborative game in their own tight-loop media ecosystem.

From Bitcoin, we see that showering acolytes in riches is a surefire path to viral growth.

And in both cases, we see the powerful narrative lure of toppling a corrupt elite.

How might other movements co-opt these tactics to provide their members meaning?

Imagine a Climate movement that argues for abundant, free, clean energy. Imagine that cultivating alternative energy -- through home solar or wind -- is a path to profit and status.

Imagine a reinvigorated Cult of the Entrepreneur. Imagine that it paints a vision of new, socially responsible enterprises toppling corrupt incumbents.

Imagine a social progressive community that feels more hopeful and less -- well -- Old-Testament God vengeful.

Imagine an online artistic community that allows artists to feel empowered and (potentially) enriched by their self-expression.

And look: blind faith in any narrative, of any kind can be dangerous. But belief in the grand narrative sweep of the World and our ability to both join and inflect the arc of history is a fundamental human need. Detractors might call it “main character syndrome,” but most of us would just call it “being a human.”

Ours, after all, is a meaning-making species.

The internet need-not only connect us to 15 second videos. It should also connect us to meaningful stories that shape our lives and the world we live in. That’s a future where our psychological needs for purpose and community are as well-met as our physiological needs for food and safety. It is, in short, a future that’s worth living.