It takes a village to raze an oligopoly (gmgn supply co.)

An unlucky social theorist, the rise of consumer culture from Procter & Gamble to Kylie Jenner, and a vision for a community driven future.

A Really Brief Economic History of Humanity

Do you have a favorite graph or are you normal?

I’m on Team Favorite Graph. And this is mine:

Pretty remarkable, right?

For thousands of years, humanity survived in abject poverty and then POW! – the Big Bang of Capitalism!

Why did this happen? Historians don’t really have a single answer. Some think it was reform of the intellectual property regime or the birth of a modern banking system. Some think it was the scientific revolution of the preceding centuries. But I’m going to offer a slightly different theory – borrowed heavily from what I vaguely remember from a college Economic History seminar.

Those institutional and intellectual revolutions were necessary but not sufficient. To drive the economy forward, we needed the insatiable desires of the consumer. And the 19th Century was the first time that that force could be unleashed.

To understand why, we need to meet Rev. Thomas Malthus.

Mr. Malthus holds a unique distinction in world history. He discovered one of the most iron-clad laws of human economics at the exact moment that it would prove no longer relevant. Unlucky guy.

In 1798, his Essay on the Principle of Population captured the mechanics that determined living standards throughout human history. It worked like this:

During good times, humans celebrate by having lots of kids and making more humans. But the supply of food tends to stay pretty fixed.

So now we have lots of humans fighting over less food. This leads to war, famine and disease.

So people have fewer kids. This makes food per person go up once again.

So people celebrate by having more kids…

This is known as the Malthusian Trap.

Malthus wrote in 1793. He believed it explained why humans were stuck in a constant cycle of misery. And the cycle had explained history pretty well up to that point. But it did not explain the boom that was beginning at the end of the 18th century.

Advances in agricultural machinery allowed citizens of the UK to produce surplus food. For the first time, humanity could aim for more than subsistence.

This was a pivotal moment. And human history might have looked a lot different.

Freed from the Malthusian Trap, humanity could have chosen what John Stuart Mill called the “stationary-state.” We could choose a life of leisure, reduced work hours and greater time for family and community.

LOL.

We did not choose this path. After all, there were things to buy.

So instead, we chose the world of Adam Smith.

In the 19th Century, British citizens developed a taste for new foods, new fashions and new household goods. The Malthusian Trap defined the first few thousand years of human civilization. The Consumerist Loop would define the next two hundred.

And so began a new, positive-sum feedback loop of consumer acquisitiveness/product development. Here’s how it works:

We see new things that our friends have. We want those things.

To get those new things, we have to earn a lot of money. So we help create other new things.

Soon there are many new things that we want! So we have to work even harder!

And around and around the consumerist cycle goes.

And, look, it’s easy to be cynical about this greed driven process, but we should be careful before making a judgment.

Your clothes, your TV, your fancy apartment, even your medication are products of a world built by Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand. And while, sure, time with family and friends would be nice – we also really do like our nice stuff.

Today the consumer economy includes well … everything. But in its early days, the industry focused on two key verticals: clothing (textiles) and consumer packaged goods (CPG). CPG includes those goods that customers use and replace frequently. It spans from food and beverages to cosmetics and household goods.

In 2021, the CPG (Consumer packaged good) industry accounted for $1.5 Trillion in the US alone. The intrepid entrepreneurs who saw the potential of these daily staple products got their start in the 1800s. To learn how they built those empires, we need to travel to Cincinnati in 1837.

Procter & Gamble and The Rise of Consumer Goods

William Procter was a candlemaker from England. He arrived in Cincinnati in 1832 and shortly after, married Olivia Norris. James Gamble was an immigrant from Ireland who settled in Cincinnati with his parents in 1819. He started a soap shop and soon married Elizabeth Norris, Olivia’s younger sister.

Alexander Norris -- Will and James’s shared father-in-law -- realized that the boys both needed animal fat for their goods. He suggested they join forces to achieve a small economy-of-scale in manufacturing. Procter and Gamble was born.

P&G was a local outfit, at first, operating out of a store in downtown Cincinnati. But the partners leveraged their scale from joint manufacturing to out-compete local rivals. Then they began to expand. Cincinnati was well-positioned on the Ohio River and the pair began selling their products down-river. When railroads came to Ohio in 1848, the company started selling to the East Coast, as well. In the 1850s, the company started using a star and moon logo that would persist into the 1990s. The firm grew faster during the Civil War as it won a contract to supply Union Troops. Then, in the 1880s, it began to invest in new product development focusing on cheaper soaps.

This sets a template for feedback that we can see in every CPG giant.

Early strength in manufacturing and distribution provides a competitive advantage.

This advantage allows investment in branding and new product research to differentiate products.

Differentiation of products provides the ability to accrue greater profits.

Those profits can be invested in manufacturing and distribution. This serves to further solidify the conglomerate’s advantages.

Major Conglomerate Playbook

This playbook was copied by all of the major players, and the returns to scale were so powerful that the CPG landscape looks like this today:

11 major conglomerates own almost all of the major brands that you grew up consuming.

In the early 2010s, these empires and their shared business model faced their first real challenge. Easy access to factories in Asia eroded the giants' scale advantage in manufacturing. Meanwhile, the internet offered a quick path to consumers that bypassed retailers.

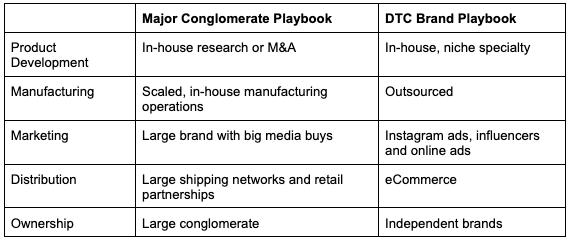

Brands like BlueApron, Harry’s, DollarShaveClub and SmileDirect use this playbook:

This, in turn, has allowed them to compete in an arena where they can dominate the majors: brand and product. But, over time, DTC brands have run into their own challenges.

In the early 2010s, low-cost digital ads helped these businesses to scale rapidly. But as incumbents moved online, digital ads became more pricey. So DTC brands have started to turn more to influencers to launch their brands.

As a result, influencer marketing has grown at an insane pace. The industry did $1.6B in business in 2016. By 2021, it was doing $13.8B.

Influencer marketing is great for brands, but a faustian bargain for influencers. They trade their brand equity for a quick pay-day, but get no long-term value in return.

That’s why the most successful influencers have taken on brand-building themselves.

Emily Weiss’s Glossier is worth ~$1.8B.

Rihanna’s Fenty brand is preparing for a $3B IPO.

Kylie Jenner sold 51% of Kylie Cosmetics in 2019 for ~$600M.

The DTC brands compete by building their brand equity. But influencers already have equity to spare. The larger their brand, the larger the monetization potential. But this system also has an interesting contradiction.

The most effective influencer marketing comes from smaller influencers. But these influencers lack the scale to start their own companies.

This begs the question: what would it look like if there was a brand built of, by and for a community of micro-influencers?

gmgn supply co.: Village-to-Consumer Brands

A few weeks ago, I spoke with Maggi Xu, a leader of gmgn DAO – the first DAO trying to build a CPG company. gmgn's vision of community-centric consumer businesses is a natural evolution from the DTC brands of the 2010s.

gmgn started with a tweet:

In real-time, the replies began to lay the foundation for a new company. Emily Elise, the founder of OffLimits Cereal offered to help produce the product. The media agency, Funday, kickstarted a new organization – gmgn supply co. – to get things moving. They were joined by a team from outside the agency including Maggi, Emily, Deb Lutz and Robert Lendavi.

gmgn is organized around a hypothesis that motivates much of Web3. Traditionally, businesses looked for product-market-fit. They then used traction to bootstrap a community of fans. But Web3 inverts this model. It argues that companies should start by building an engaged community of stakeholders. Then they should develop products that reflect the values of their community. The engaged community becomes both your shareholders and your best evangelist.

In keeping with this model, gmgn is organized to promote community ownership. 40% of revenue will be distributed to DAO members. 19% will go to the collectively managed treasury. 1% will go directly to an organization aligned with the group’s values – the World Food Programme.

This “Community-First” strategy has a few potential advantages.

Young consumers choose brands that reflect their values when choosing where to shop. Large companies invest millions in learning what those values are and speaking their language. But a brand developed by a community of that generation's influencers can speak their language natively.

Furthermore, rising online marketing costs are less of a risk to a community owned brand. A brand owned by its evangelists does not need to pay for further marketing.

This model also opens the door to some interesting organizational innovations. For five years now, “stakeholder capitalism” has been a buzzword. It promises a more responsible capitalism. A company is accountable not only to its shareholders, but also to its customers, its employees and the broader world.

Community-owned businesses are inherently stakeholder capitalists. Products designed to meet the needs of its community ensure that shareholders are also customers. Customers, in turn, are likely less willing to sacrifice the quality or ethics of their product than a disengaged shareholder. This could lead to a broader capitalism -- where engaged shareholders care about more than just the bottom-line.

Of course, to achieve that vision, these organizations need to show they can out-compete traditional firms. That’s no easy feat. Community run organizations are inherently slower and messier than private companies.

Private companies have absolute clarity on their goals. Stakeholders may complain about ESG targets, but ultimately, most investors only want a return on their dollar. As a result, the company knows what it is trying to achieve, and that tight focus leads to effective results. Moral compromises are an expedient – if unsavory – tool for large companies.

DAOs do not have that luxury.

Imagine a DAO that claims to have high labor standards deciding whether they want to sell through Amazon Distribution. As tempers flare between those who support the move and those who don’t, folks decide to rage-quit the community and share their disappointment on Twitter. An internal debate could become a toxic Twitter war. The same influencers that provide free marketing could become loud activist investors. Those that live by community sentiment are always at risk of dying by it, too.

This begs the real critical question: What do Americans really want from their brands?

In an age where Disney, Coca-Cola and every major company is being dragged kicking-and-screaming into culture wars, it’s unclear that the answer remains, “just good products at cheap prices.” But if consumerism is heading toward a world where our purchases better reflect our values, DAOs will have the advantage.