Do Your Own Research: The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories

Why we believe conspiracy theories and how we can stop the crazy.

I spent this weekend bingeing The Traitors on Peacock.

A group of 20 contestants tries to suss out three traitors amongst them while living in a dreary castle in Scotland. The traitors “kill” one of the contestants every night. If the “faithful” find and vanish the traitors before the traitors kill them all, they win a $250,000 prize. If not, the Traitors split the prize. It’s like Mafia, Werewolf and Among Us had a love child with MacBeth. It’s wonderful.

Each episode, the paranoid contestants are grasping at straws to find a traitor. Every gesture, every sentence is rendered meaningful. There are no coincidences to the paranoid mind.

And today’s internet – above all else – is paranoid. That paranoia might have started on the fringes – in QAnon forums and 9/11 Truth websites – but it has moved decisively into the mainstream. It has even infected many of the internet’s main characters.

Elon Musk got in on the fun in October when he implied that Paul Pelosi had not been attacked by a crazed extremist but was, instead, a victim of a lovers’ tiff with a male escort, writing: “There is a tiny possibility there might be more to this story than meets the eye.” He linked to a story containing the claim.

Elon-friend, investor and inventor of the modern browser, Marc Andreesen, also tweeted:

I find this trend fascinating (if, y’know, terrifying).

Because this season of Twitter and this season of Traitors both highlight that we’ve been lied to about who believes conspiracy theories.

For years, the dominant narrative has been that conspiracy theories prey on society’s most vulnerable. The internet, we’re told, profits off these poor souls’ fears by spreading extreme paranoia and mass-delusion to generate ad clicks.

Bad, Facebook. Bad, Twitter.

If you work on digital coordination technologies – like social networks or DAOs – this should give you pause. I subscribe to a baseline optimistic view of human nature. I believe that online communities are overwhelmingly a public good. I believe that giving online communities tools to translate their values into real world impact is a profoundly positive step for humanity that will lead to a world that better aligns with the angels of human nature.

But if I’m wrong – if people are crazy and social networks are making them craziers, then the invention of online community tools and tools for turning belief into capital and capital into action (like crypto and DAOs) are likely to lead to more events like January 6 or the riots in Brasilia this month.

Considering this question – whether the internet makes dangerous conspiracy theories more dangerous and if that impact can be tamed – has become one that keeps me up at night. This week, I decided to share what I’ve learned.

The Paranoid Style in American Politics

“American politics has often been an arena for angry minds,” Richard Hofstadter wrote in Harper’s. “In recent years we have seen angry minds at work mainly among extreme right-wingers, who have now demonstrated in the Trump movement how much political leverage can be got out of the animosities and passions of a small minority.”

This essay isn’t recent. It was written in November 1964. The only word I changed was replacing the name “Goldwater” with the name “Trump”.

And even then Hofstadter’s point was that the “paranoid style” was a persistent feature of American politics.

In 1951, Joseph McCarthy blamed the “perilous” standing of the United States on communist infiltration. In 1895, the Populist party complained that an international cabal of gold speculators was manipulating markets and holding the working class hostage. Before that, it was fear of Catholics, Masons and the Illuminati infiltrating the country and steering the ship of state.

Deep state. QAnon. It’s all the same story. It’s a paranoid delusion as old as the Republic itself.

But, if that’s the case, we still need to reckon with why these conspiracies seem so prominent today. Isn’t the internet fanning the flames of these conspiracies? Isn’t it the case that a fringe media can increase its distribution and further radicalize good, honest Americans?

It’s a good story. But the problem is… it’s just not supported by the data.

In a July 2022 study, Joseph Uscinski, et al. published an analysis of surveys tracking beliefs in various conspiracy theories over time. The time horizons ranged from several months (in the case of COVID conspiracy theories) to several decades (in the case of JFK-assassination theories).

What is new – what has changed – is that we are focusing on these stories with increased urgency. That’s partially because we had a President who openly flirted with them. It’s also because – through the magic of social media – we are finally able to see what our fellow countrymen believe en masse. And it turns out, people be crazy.

So what looks like internet virality is really just internet transparency. For the first time, we can actually see how crazy our fellow countrymen are. And the answers are just a bit shocking.

Which prompts two questions for me:

If Americans have always been conspiracy theorists, then why is it that we are so vulnerable to conspiracy thinking?

If we can finally see all these conspiracy theories operating in the open, then can we learn how to protect ourselves from them?

Question 1: Why are we so vulnerable to conspiracy theories?

In a separate paper, published last month in Nature, Uscinski analyzes the characteristics that correlate with beliefs in conspiracy theories.

There are some obvious influential personality traits – populism (distrust of authority), Manichaeism (belief in absolute good and evil), and the dark triad: psychopathy, Machiavellianism and narcissism.

It seems unsurprising that people that believe in absolute good/evil and have dark personality traits are likely to believe in conspiracy theories. Psych 101 tells us that we see things as we are not as they are.

People who believe in good/evil and have a tendency toward manipulation and anti-social behavior themselves are likely to project those traits onto everything they see.

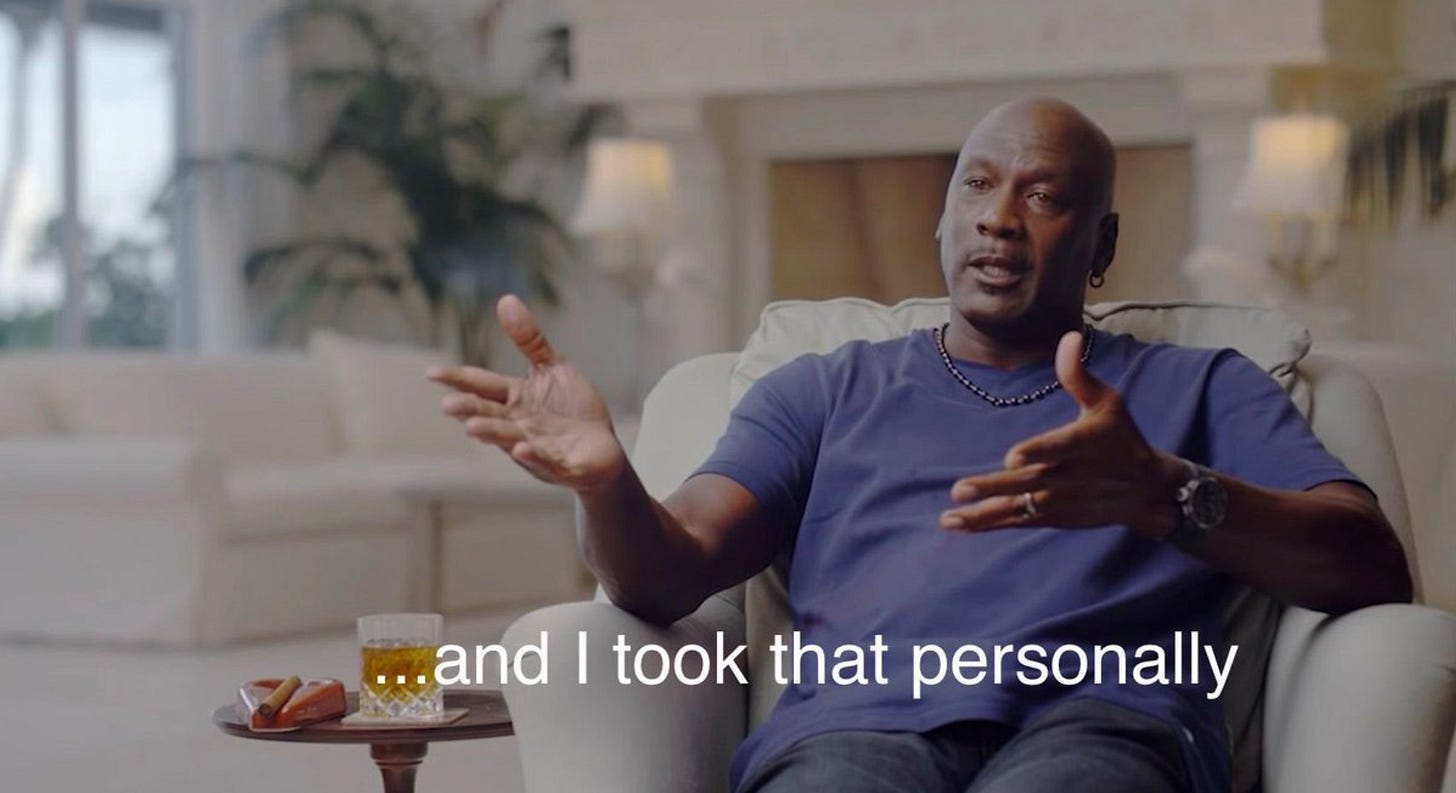

I like to think of this as the “Michael Jordan” theory of conspiratorial thinking. As Jordan was famously memed (and misquoted) as saying:

People with narcissistic traits believe every slight is about them. If an unfavorable news story is published (Elon), you’ll tend to believe that there’s a conspiracy against you. If globalization has eliminated your job, it must be because someone wants to destroy your community.

People with their own anti-social traits are likely to imagine that they would do something sinister with power, and thus are likely to see sinister intent in other powerful people. To the paranoid mind, there are no coincidences, only personal attacks. Like Michael Jordan, the paranoid mind invents a pretext for revenge and anger. Unlike Michael Jordan, they take to the internet rather than the basketball court.

If I dislike someone, I’m more likely to believe or want to believe they’re doing something sinister. But it’s here that an important tactic of conspiracy theory growth comes into play – guided apophenia. It is best described by game designer, Reed Berkowtiz, describing an early game of his that involved a treasure hunt:

“The object they were looking for was barely hidden and the clue was easy. [...[

As the participants started searching for the hidden object, on the dirt floor, were little random scraps of wood.

How could that be a problem!?

It was a problem because three of the pieces made the shape of a perfect arrow pointing right at a blank wall. It was uncanny. It had to be a clue. The investigators stopped and stared at the wall and were determined to figure out what the clue meant and they were not going one step further until they did. The whole game was derailed.[...]

I stared in horror because it all fit so well. It was better and more obvious than the clue I had hidden. I could see it. It was all random chance but I could see the connections that had been made were all completely logical. [...]

These were normal people and their assumptions were normal and logical and completely wrong. [...]

QAnon grows on the wild misinterpretation of random data, presented in a suggestive fashion in a milieu designed to help the users come to the intended misunderstanding. Maybe “guided apophenia” is a better phrase. Guided because the puppet masters are directly involved in hinting about the desired conclusions. They have pre-seeded the conclusions.”

What’s new about the internet isn’t that it spreads beliefs in questionable ideas. That happened long before we invented dial-up. What’s new is the ease with which individuals can “do their own research” to confirm misleading clues laid out for them by a puppet master. And we believe things we research for ourselves, especially when it aligns with our preferred worldview. Confirmation bias, after all, is a hell of a drug.

In a 2021 letter published in Journal of the American Medical Association, researchers analyzed public Facebook groups that were spreading COVID misinformation. They expected to find scientific illiteracy. Instead, they found a surprising degree of savvy. People were deploying statistical techniques on public datasets to “unskew” data to arrive at their preferred conclusions.

The people who believe in conspiracy theories aren’t dumb. They’re motivated reasoners. That distinction is critical when we think about how to combat misinformation.

Question 2: How can we protect ourselves from believing in conspiracy theories?

The internet has actually provided us a tremendous gift for fighting misinformation. For the first time, we can see the tactics used to evangelize. In the process of spreading, these systems of belief make themselves legible to us, and in doing so, they expose ways to protect ourselves from their corrosive effects. Social media is not just a vector of infection, it’s the microscope that lets us see the virus and visualize its weaknesses.

So far we’ve spotted two strategies to intervene.

The Best Medicine is More of the Disease

If there’s one ironclad finding on how to combat conspiracy theories, it’s this: you can’t persuade someone by showing them evidence that they’re wrong. Why? Because attacking someone’s beliefs is perceived by the mind as an attack on the individual themselves.

In 2016, researchers Kaplan, Gimbel and Harris published an article in Nature, showing that you could literally see the brain shutdown its networks for processing new information and changing beliefs when threatening counter-evidence to a core belief was offered.

So what do we do instead?

According to an NPR interview with Diane Benscoter, a former cult member who now helps deprogram conspiracy theory believers, the first step is to make the other person feel safe. Then you build on the idea of “doing their own research.”

Instead of offering an alternative rendering of the facts, you can start seeding some ideas that enable the person to do their own research. If a person talked themselves into a conspiracy, they’re going to have to talk themselves out of it. And the best way to do that is to gradually guide them to poke holes in the conspiratorial trap.

Inoculation

The best defense is preventing the disease from taking root at all. Most researchers advocate techniques they call “inoculation.”

Just like its biological cousin, misinformation inoculation exposes individuals to weakened versions of misinformation to train our psychological immune system to recognize techniques used to manipulate our beliefs by teaching people about the rhetorical strategies that bad actors employ – emotionally manipulative language, common logical fallacies, false dichotomies and scapegoating.

The early results of this approach are promising. An article published in Science tested the efficacy of a series of YouTube videos on training people to recognize and refute misinformation. Showing the videos as ads on YouTube, and then testing the viewers’ ability to discern misinformation, showed that viewing a single video could move misinformation recognition by ~9%.

That’s not enough to end the Paranoid Style in our politics. But it’s a sign that we might not be doomed to a world of QAnon fantasies forever.