Escaping the Gossip Trap: DAOs vs. the Mob

Erik Hoel's Gossip Trap. The emergence of civilization in online communities. A future of sovereign online communities.

Back to High School

I don’t know what the prehistoric savannah was like for early homo sapiens, but I can’t imagine it was a lot like Twitter.

And yet… I find something persuasive in Erik Hoel’s recent argument about the Sapient Paradox.

The Sapient Paradox asks why – if homo sapiens evolved into its present form, with all of its current cognitive skills, some 200,000 years ago – it took us until 10,000 BC to develop civilization. It’s a question that many “Pop Historians” have wrestled with over the last 100 years.

Most theories appeal to Dunbar’s Number. Dunbar suggests that a human being can manage only 150 social relationships at any one time. This limit meant that our natural social organization – the tribe or village – could only scale to 150 people or we would cease to be able to regulate it via social relationships. So we were naturally predisposed to stay in this state and ill-equipped to invent means to move beyond it. Instead, we existed for 200 millennia in “perpetual high school.” As Hoel explains:

“After all, in high school there is a clear social web but no formal hierarchies. And while there is a social hierarchy, it’s not ordinal—you couldn’t list, mathematically, all the people from least to most popular, like you could with a formal hierarchy. It’s more like everything is organized by a constant and ever-shifting reputational management, all against all. And there’s actually a lot of evidence, even just in what the Davids themselves introduce, that fits with the idea that our initial condition was something like anarchist bands organized by raw social power only.”

Keeping society ordered in this way required all of our brainpower. It created a social analog of the “war of all against all” and prevented the emergence of art, science, or any of the other fruits of civilization. Gradually - our economies linked cities spread across continents. Our ambitions for conquest created empires that far exceeded 150 people. So we needed new ways to organize society.

We created different social contracts. We created hierarchy. We created reputation mechanisms. We created legal and social accountability to crown, country and commonwealth. We scaled beyond Dunbar’s Number.

And life was good. Sure, we still gossiped about the 150 people closest to us, but we let laws govern our society outside our immediate circle. But then social media shifted the balance. They provided another way to escape Dunbar’s Number.

Computers can hold the social order in memory for us, and therefore lift the constraint imposed by Dunbar’s Number.

As a result, we can gleefully revert to a world characterized by our evolutionarily favored strategy of Gossip. We can rebuild a global version of the Gossip Trap. Twitter as perpetual high school. Twitter as war of all against all.

This is where Hoel’s argument becomes relevant to our modern era. He claims that Twitter has forced a reversion to our prehistoric forms of governance: gossip and raw social power. And just like our great^n grandparents, we are now stuck in a perpetual struggle of virtue signaling, trolling and cancelling.

If we’re to have any peace, we need a new way out.

The First State Rises

So where does our march of civilization begin this time?

We can look to history.

With due respect to the Athenians, the ancient world was mostly a place of autocracy. Legitimacy in the ancient city-state was conferred by two particular narratives: divine right/“founder privilege” or raw social power (popularity/physical might, etc).

Our early attempts at digital civilization look much the same.

We cry out for Mark Zuckerberg to fix Facebook by vanquishing our political enemies. Why? Well he built the damn thing and shouldn’t God be just?

We look for state intervention as a deus ex machina! Why? Well - they seem all powerful!

But as our digital commons moves from anarchy to authoritarian to – with the advent of cryptocurrency – anarchic capitalist, we suddenly have need for a more nuanced social contract. We need a digital rights system that can protect our interests against raw social power. We need a new escape from the Gossip Trap.

The good news – it seems one is starting to emerge.

The bad news – the emergence of historical nation-states neither eliminated war nor ushered in a utopia of tolerance. It just created a new type of conflict. And while history may not repeat itself, it sure has a nasty habit of rhyming.

Beyond Mob Rule: The Case of Brantly Millegan and ENS

The core of civilization is a justice system. It is how the state protects citizens and their property from violence. It is also how the state protects the wrongfully accused from vengeance. Legitimate civilizations encourage a well-considered, mutually agreed upon process for handing difficult cases.

All of this brings me to the case of Brantly Millegan and ENS.

Brantly was, until Feb. 2022, a relatively popular figure in the Ethereum community. He was one of the most out-spoken leaders of the Ethereum Naming Service organization (inventors and stewards of those “.eth” domain names).

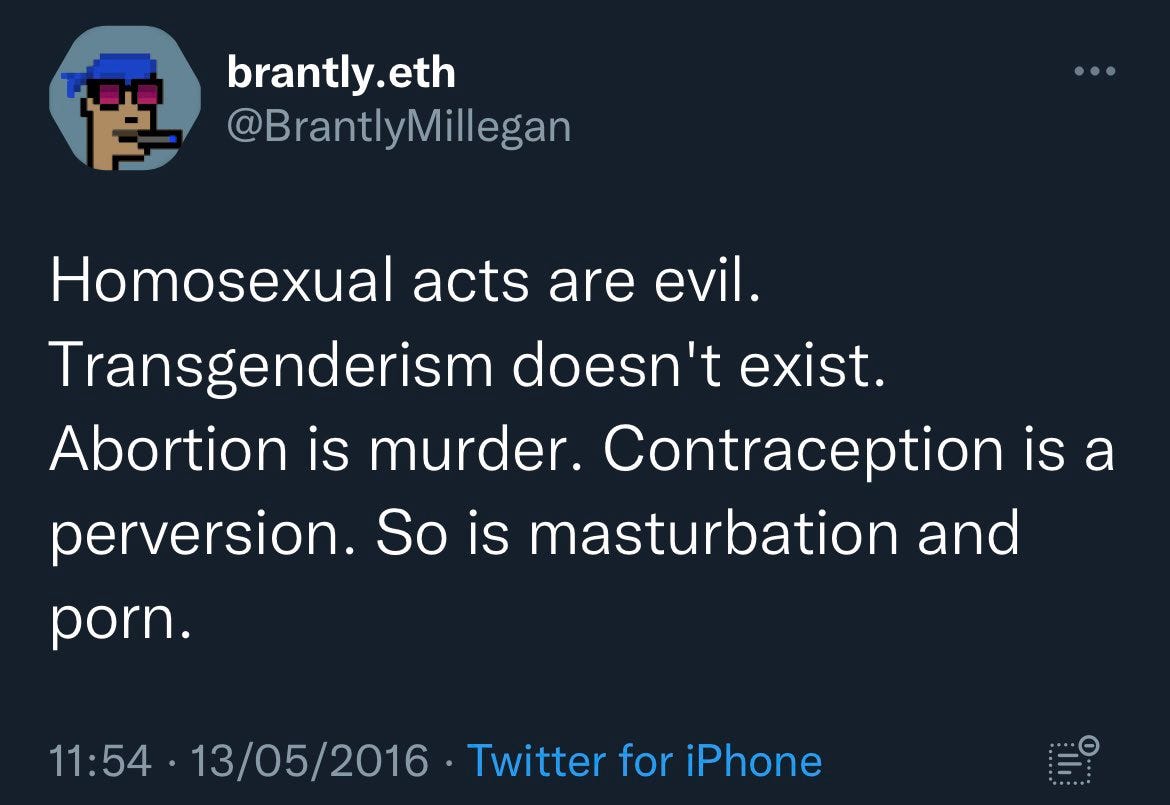

But in early February, some folks dug up some old Brantly tweets, including this gem:

The ENS and Web3 community were predictably outraged.

Rather than retreat, Brantly retweeted. He wrote, “Not really interested in debating theology right now, but what I believe is the mainstream traditional Christian positions held by the world’s largest religion. it’s not exactly fringe.” That went over about as well as you might expect.

And so, predictably, the mob formed. Crypto Twitter wanted his scalp. Now – I want to be really clear here because this is important. I’m not interested in whether the mob was right (I’d argue they were).

I’m interested in how raw social power was channeled into a reprisal against Brantly when a contentious issue arose.

And the ideological issues this case raised were contentious. Crypto is built on an ideological opposition to systemic censorship. Free speech is chief among the virtues of this community.

But ENS is also, first and foremost, a community. A community, by definition, has values and norms. And much of the ENS community was deeply offended by Brantly’s anti-LGBT rhetoric.

The community found itself at odds between its libertarian leanings and its commitment to defend the disenfranchised people it claims to serve.

How does any community deal with these tensions?

In Web2, those challenging Brantly would have a few options of which to avail themselves. They would have asked Twitter to suspend Brantly’s account (they did, no dice). They would have hoped to bring a social media mob’s worth of pressure on his employer to force his removal (they did and they won). Their success or failure would be determined by the quality of their appeal to those in power. The raw social power of the mob was their only choice.

But Web3 confers autonomy for these communities to self-regulate. Self-governance means that Brantly’s case could be handled by the community itself. So it’s worth examining exactly how this DAO utilized that autonomy.

ENS is administered by two groups.

First, there is the True Names, Ltd. corporation – the founders of ENS where Brantly had been Chief of Operations. Second, there was the ENS DAO, the community charged with on-going governance of the protocol.

Within 24 hours, Brantly was fired by True Names. The mob had gotten its scalp. Or had it?

Because what happened next was truly novel. Social pressure met the community’s social contract. In line with its Community Charter, DAO members initiated the process to remove Brantly. But rules required the vote to go through normal channels, and that meant a significant period of delay.

Voting began three weeks later, on February 28, and finished on March 5. Brantly survived removal by a margin of ~6%.1 The tempers of the mob cooled enough to allow for a transparent, democratic process to take place. Online. Among people who did not even know each other in real life.

I honestly don’t think anything like this has ever happened on the internet before. It’s a watershed moment. And it provides a template for what an escape from Hoel’s Gossip Trap could look like:

Online communities that practice self-governance in line with these principles:

Right to Self-Govern - Communities of sovereign digital citizens can develop a clear charter and set of rules that each member agrees to abide by;

Right to Due Process - In the event of violations of that Social Contract, members can initiate a trial against the offending individual who then has the right to their community’s due process;

Right of Transparency – Votes are all shared on-chain so that they are equally visible by all community members.

Right to Exit - Individuals may exit these communities at any time for any reason. Those who disagreed with the community’s decision could vote with their feet.

Imagine that the social protocols that you use, the company that you work at, the community groups that you frequent, all had digital processes that balanced the rights of the accused and the accuser. Imagine that all of them had some set of “member code,” that you opted into upon joining.

In this world, the high-pressure thrust of the mob to “de-platform” or to cancel would be forced through transparent processes that balance the rights of the accused against the rights of the community. We would still hold people to account, but we would so according to the terms of the communities that they have chosen to join.

Of course, not every community will have the same standards. R/Libertarian will govern itself very differently than r/Socialism. The key to coexistence will be respect for digital sovereignty. And that brings us back to 17th Century West Germany.

The Westphalian DAO System

At the Conclusion of the 80 Years War, Europe crafted an international order that has – in some ways – endured to the present-day. The “Nation State”/Westphalian system required each state to recognize the sovereignty of every other state. For the first time, different Kings recognized each other’s sovereignty. These Kings recognized the rights of the Dutch to rule the Netherlands, the Prussians to rule Prussia and the Spanish to rule Spain.

Within their own borders, each King was… well… King.

A digital Westphalian system would operate in the same way.

While we may not like what is said in the 8Chan or Woke communities of the internet, we will recognize the sovereignty of those communities to govern their own members. We will develop a notion of “Network Sovereignty.”

And when we choose to cross borders into shared spaces or into another network, we will also have to recognize that community’s sovereignty.

If you wish to access a Discord or a Message Board or a VR space governed by a community, you will agree to abide by the host’s norms. In the physical world, if you commit crimes in another country, you are subject to imprisonment. That does not exist in the network state. But asset custody does. By connecting your wallet to a network, you will collateralize your assets as a sign of good-faith. You will literally become subject to the community’s rules and liable for your actions.

The Westphalian system can actually extend further. Communities will likely also develop their own network alliances that are sympathetic to their worldviews. They may create extradition agreements – ensuring that the crimes recognized by one are reciprocally prosecuted by others.

At the same time, communities will refuse to exchange services or trade with ideologically hostile communities.

Like the international order, a future internet fragmented into sovereign networks is not a utopia. Asset theft, espionage and memetic war will rage across a new fractured internet – much like it does between the US, China and Russian spheres today. But the advantage of such a system is likewise clear. Politics will begin at the network’s edge. Inside your digital borders, peace can reign.

There are two caveats to this result to flag:

Brantly only survived because he used his tokens (which made up ~10% of the vote) to vote for his own protection.

Community leaders, who were close with Brantly, decided to abstain. That was also determinative.